I’m sure you’ve been hearing a lot about the Science of Reading lately – maybe your school is implementing Science of Reading components already, or maybe you are being asked to work a few elements into your schedule.

The Science of Reading is a large body of research about how reading happens in the brain and how we can most effectively teach reading. The Science of Reading is often abbreviated as “SoR.”

The thing about the Science of Reading, however, is that it’s actually not all “new.” Some of the research has existed for decades! But that said, if you started teaching in the pre Science of Reading years, it can be overwhelming to figure out which pieces of your instruction still align with the research.

Maybe you have activities or practices you’ve done for years (or even decades) that you’re thinking about: “This has always worked for my kids. Can I keep doing it?” So when it comes to the Science of Reading, what literacy practices are in and out?

In this post, I’ll cover many literacy areas – oral language, phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension, and writing – and discuss the “old way” versus the “new way” of doing things when it comes to Science of Reading!

However, please know that when I say the “old way,” it’s just a way of describing what some (not all) teachers may have done in the past. I know that I personally followed many elements of the Science of Reading for years and years, before SoR became popularized – and you may be in the same boat!

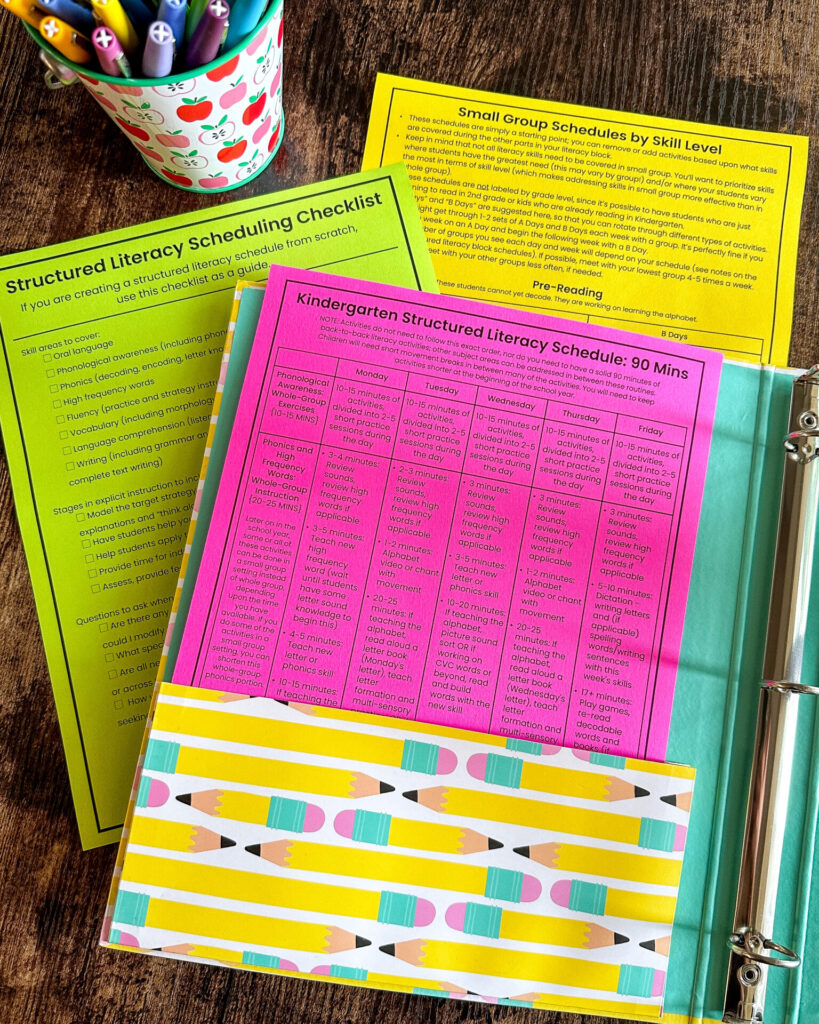

Everything I’m going over in this blog is covered (in more depth!) in a course I offer called “Implementing the Science of Reading in K-2: Blueprint for Your Structured Literacy Block.” By enrolling, you can master the Science of Reading and feel confident that you’re giving your students all the skills they need to be successful!

Oral Language

Oral language is spoken language, the way we communicate through talking. This includes 5 components: phonology, vocabulary, morphology, syntax, and pragmatics. (For more on these definitions and other terms, check out What Do All These Terms Mean? A Dive into the Science of Reading!)

“Old Way”

One practice that is out is ignoring oral language altogether! We do curriculum mapping to make sure we cover all of the reading, writing, and math standards for our students, but how often do we map out a plan for addressing oral language skills?

Oral language is often overlooked in literacy instruction. However, if children do not understand oral language, they will not comprehend language when it is written down, in text. Also, many studies show that oral language proficiency in the earlier years predicts later reading comprehension proficiency (Castles, Rastle, & Nation, 2018).

“New Way”

A practice that is “in” is to explicitly model and teach conversational skills. Model, explain, and practice skills like:

- taking turns

- eye contact and body language while listening

- asking questions for clarification

- voice volume

Then, provide students with many opportunities to talk during the day. Turn and talks with partners allow students a time to share their own ideas through oral language and also listen to others talk. You can also include sentence starters like the ones pictured below to support turn and talks.

Phonological Awareness

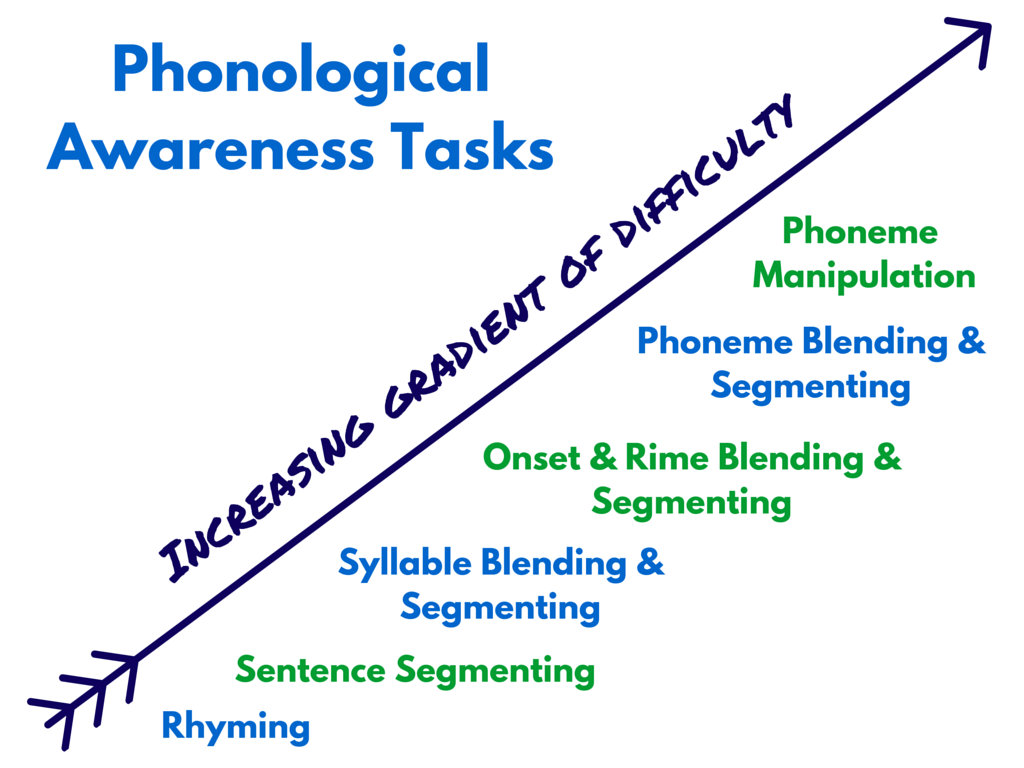

Phonological awareness is the ability to identify and work with the sounds of spoken language. Reading and spelling require students to understand the connections between sounds and letters. However, we first have to raise students’ awareness of the sounds in words to facilitate that reading and spelling!

“Old Way”

Sometimes teachers only cover phonological awareness (things like rhyming, syllable segmenting, phoneme blending) when students are really struggling. Or sometimes, teachers don’t cover phonological awareness at all! Instead, maybe that’s “saved” for a reading interventionist, in a 1:1 setting, or with one small group of students extremely behind in their reading skills.

“New Way”

I recommend covering phonological awareness daily, through explicit instruction. This means that you are explaining exactly what you’re doing, and modeling as needed. Then, students should have an opportunity to practice these skills independently. Ideally, there would be 10 or so minutes each day for Kindergarten and first grade and then 5-10 minutes for beginning second graders. These minutes do not have to be in one sitting; they can be spread out throughout the day and even during transitions. Some of these activities can also take place as part of your phonics instruction.

For activities on phonological awareness, check out my blog “5 Phonological Awareness Center Ideas.”

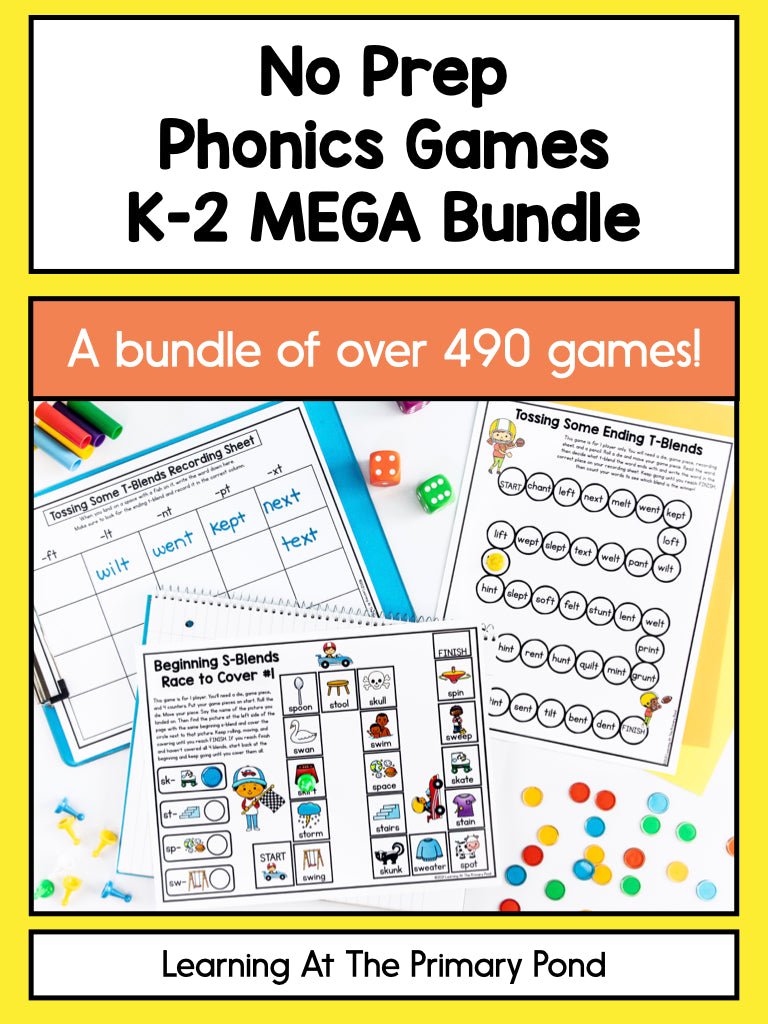

Phonics

Phonics is instruction that teaches the relationships between letters and sounds. The reason phonics instruction is so important is because the human brain is not naturally wired to match visual images (letters) to sounds- which is required for skilled reading. Phonics instruction helps to build neural pathways that humans are not born with!

“Old Way”

A practice that is “out” is using incidental phonics instruction. This means that the teacher does not follow a planned sequence of phonics skills. With incidental phonics, the teacher would mention skills/elements when they just appear in texts they’re already reading. For example, if a teacher is reading students a poem that has many examples of the -at rime, they might cover that word family.

“New Way”

On the contrary, a practice that is “in” is to use systematic instruction by following a scope and sequence. With this method, individual phonics skills (like short vowels or consonant blends) are laid out in a sequence. You then cover each skill in that sequence (ideally, moving on to the next skill only after students have mastered the current skill).

Need a scope and sequence? I’ve got a FREE K-2 scope and sequence you can use. Click here for that!

Fluency

Fluency is the ability to read accurately, at an appropriate speed, and with proper expression. Fluency is important because it frees up working memory so that students can focus on understanding what they are reading. Also, improving students’ fluency has been shown to improve their reading comprehension.

“Old Way”

Some teachers have relied on timed readings to practice and assess fluency. Students were asked to read a text multiple times while we timed them. In this sense, it was sort of a competition to see who could read through the text the quickest – or even a competition against themselves.

But the goal isn’t to speed through the text! Rushing through can lead to students reading incorrectly, as well as reading without expression. Reading speed is part of fluency, but it’s not the entire picture.

“New Way”

Instead, it’s important to teach fluency through explicit instruction. Here’s an example:

- Display a text so that both you and your students can see it. (It could be a few sentences written on poster paper or something projected for students to see.)

- State your goal. This should relate back to the definition of fluency – reading accurately, at an appropriate speed, and with proper expression. For instance, the goal could be “Read through the entire sentence smoothly.”

- Model! Show students what a fluent reader looks and sounds like. You can/should also model the incorrect way to do it. For example, I like to “read like a robot.” “The. Boy’s. Pet. Is. Named. Gus.” I even do hand motions like I’m a robot. Kids think it’s hilarious. I ask them, “Is this how we should read? Choppy like a robot?” “Noooo!!” they reply. I follow this up by explaining, “You’re right. I shouldn’t read like a robot! I want to read through my sentences smoothly. Thanks for helping me out!” And then I’ll reread, modeling fluent reading and pointing out how I scoop up words in smooth phrases.

- Provide opportunities for guided practice where students are reading fluently with you, such as echo read, choral read, or partner reading.

- Last, provide opportunities for students to practice fluency independently. This could be a student rereading the same passage multiple times with a particular goal in mind each time.

Excellent fluency instruction helps students build speed and accuracy, plus learn to read smoothly and with expression.

Vocabulary

Vocabulary is knowledge of what words mean and how they are used. No matter if a reader is a student or an adult, research agrees that vocabulary knowledge is very closely related to reading comprehension.

“Old Way”

Quite often, it can be easy to do these things when it comes to vocabulary:

- Leave out vocabulary instruction altogether! (With this, students most likely just have to guess what words mean in a text based solely on the context.)

- Try and pack tons of new words into a short amount of time. (i.e. “Let’s quickly read these 10 new words and then match the definitions!”)

- Define words as they come up during read-alouds, but never revisit them again.

These practices aren’t effective.

“New Way”

Research has shown that this is best when introducing a new word:

- To begin, provide a student-friendly definition of the word. You don’t need to have students guess what the word means.

- You can restate the definition when the word is encountered in a text if needed (i.e. in the middle of a read-aloud.)

- A single exposure to a word is not enough. Consider using a couple of days of multiple exposures of the word. This will help reinforce the word and make the meaning “stick.” Some suggested activities are:

- acting out the meaning of the word

- fill-in-the blank activities

- matching activities

- games using the new words

- encouraging students to come up with a question using the new word

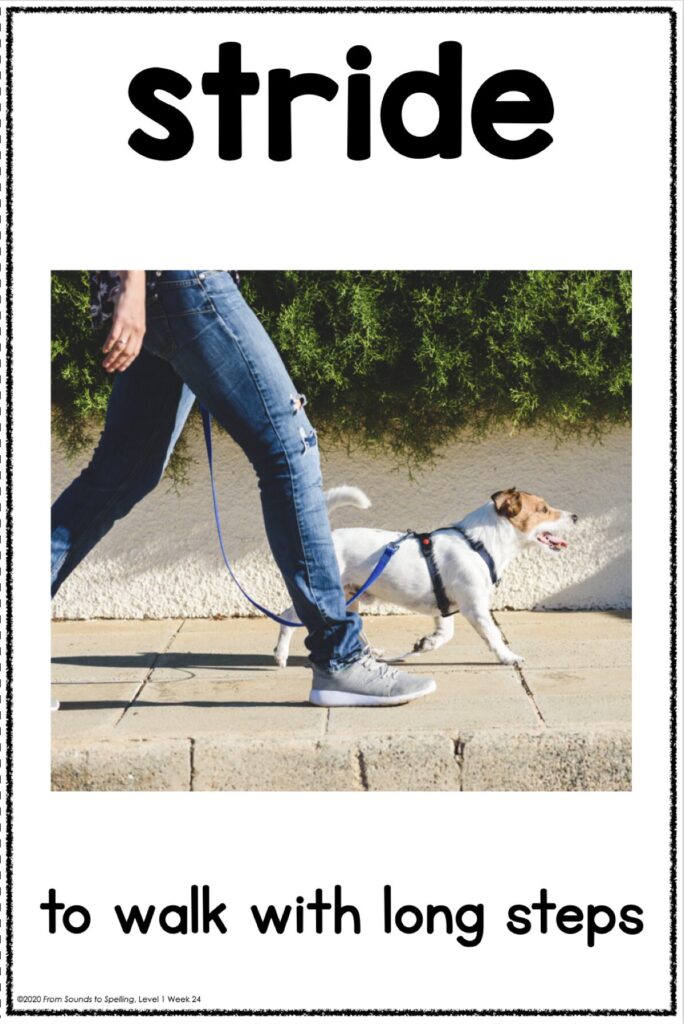

- Use visuals (like this “stride” example below) when possible!

Comprehension

Comprehension is a set of complex skills that allow the reader to understand and think deeply about a text. It’s important – it’s the entire point of reading! While we do spend a great deal of time on the building blocks of reading in K-2, we must also devote time and attention to comprehension specifically.

“Old Way”

A literacy practice that is “out” is solely teaching comprehension by having students read a passage silently, then answer comprehension questions orally or in writing. Although this can be one way to assess a child’s reading comprehension skills, this is not really teaching comprehension skills. With this practice, a student’s comprehension abilities would also be severely limited to their decoding skills. In other words, if a child had trouble reading the passage, it would be difficult to really assess their reading comprehension based on this exercise.

“New Way”

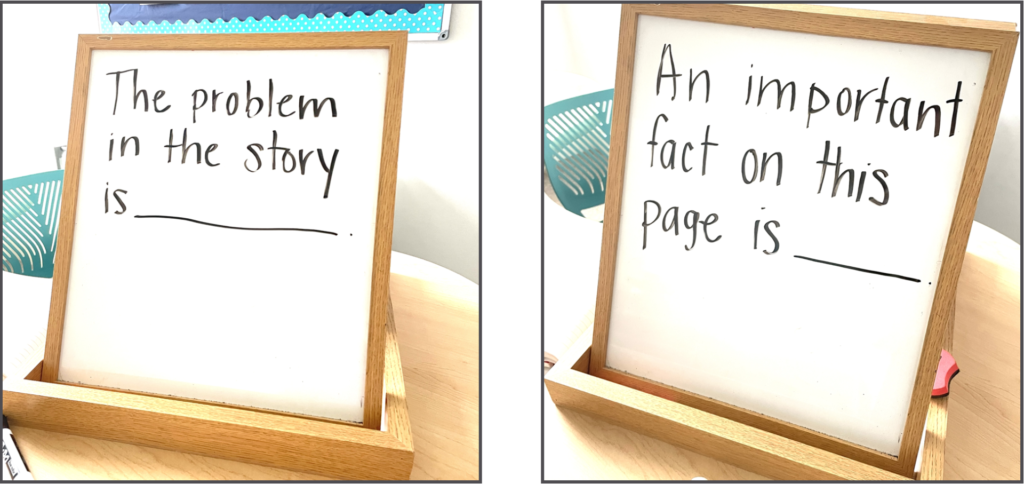

For a literacy practice that is “in,” try building up students’ comprehension skills regardless of how much they can decode! Especially in Kindergarten, first grade, and second grade, sometimes students cannot yet decode complex texts. However, we still need to be developing their comprehension skills.

The way we do this is through reading texts aloud for students to develop listening comprehension. Listening comprehension is fundamentally the same task as reading comprehension.

With read-alouds, you’ll want to teach students a comprehension skill (again, I sound like a broken record, but…) through explicit instruction. Here’s what that could look like for comprehension:

- Monday: Introduce the text. Discuss the author/illustrator and genre. Then read the text aloud. Model for students a specific comprehension strategy. Ask students about the text and summarize the comprehension strategy.

- Tuesday: Introduce the text. Discuss the author/illustrator and genre. Then read the text aloud. Have students assist you in applying Monday’s comprehension strategy. Ask students about the text and have students reflect on the comprehension strategy.

- Wednesday: Repeat Tuesday’s layout, putting a bit more responsibility on the students to answer questions.

- Thursday: Introduce the text. Discuss the author/illustrator and genre. Have students apply Monday’s comprehension strategy through drawing/writing/partner work. Provide support as needed.

- Friday: Optional to provide students with more practice with the comprehension strategy.

Writing

Writing, in its simplest form, is communicating ideas via print. Writing is an essential tool for communication, learning, and self-reflection.

“Old Way”

An “old way” of teaching writing is having students produce a piece of writing independently with fairly little guidance. Then the teacher takes a big red pen to it, marking up all of the mistakes – poor handwriting, incorrect spelling, subpar word choice. (If you experienced this as a student yourself, you might still remember to this day how that felt receiving back your paper after this process!)

“New Way”

A best practice when it comes to writing instruction is to explicitly teach writing strategies and then provide support along the way. This involves clear, systematic teaching, breaking down skills, modeling, guided practice, and independent practice. Students need instruction and modeling in the following areas of writing – planning, drafting, revising, and editing.

Here’s an example of a mini-lesson you could carry out with students:

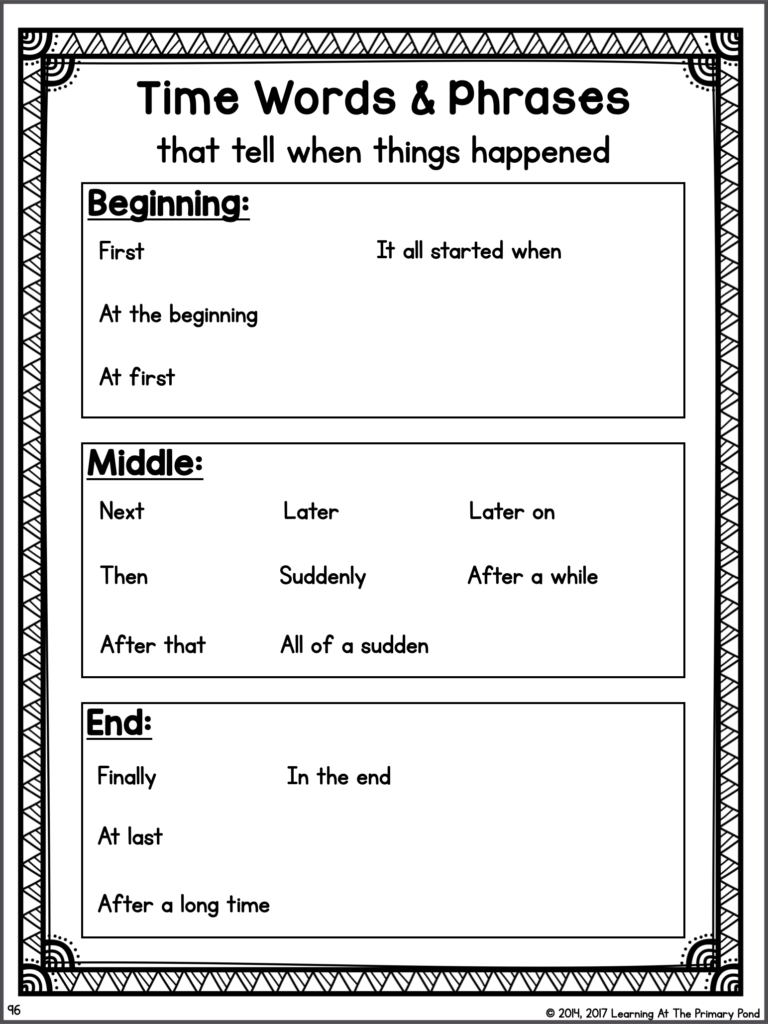

- First, explain that one way students can make their stories clearer to the reader is to use “time words.”

- Go over the poster (example below) in detail.

- Take a pre-written story of yours and model how to add in a few time words.

- For guided practice, give students another pre-written story and have them work with a partner to add in time words.

- Then, have students work independently to go through a story they’ve already written and add time words.

Through all of this, support them alongside, providing feedback in the moment as needed.

Conclusion

This was a lot to unpack regarding what’s “in” and “out” regarding literacy practices! If you want to dig in even further to make sure that your practices are up to date, click HERE to learn more about my course, “Implementing the Science of Reading in K-2: Blueprint for Your Structured Literacy Block.”

This is an on-demand professional development course for Kindergarten, first grade, and second grade teachers who teach literacy. The course will provide you with an in-depth understanding of the Science of Reading and how to apply that knowledge to create a schedule that supports all of these components we addressed in the blog!

Happy teaching!