I’m sure you’ve been hearing a lot about the Science of Reading lately – maybe your school is implementing Science of Reading components already, or maybe you are being asked to work a few specific elements into your schedule.

The Science of Reading is a large body of research about how reading happens in the brain and how we can most effectively teach reading. The Science of Reading is often abbreviated as “SoR.”

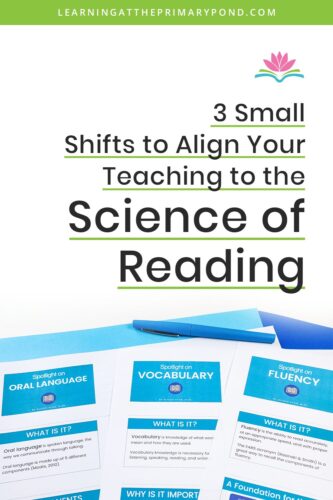

It can be overwhelming to determine which pieces of your instruction align with the research. In this post, I’ll cover 3 small shifts you can make to align your teaching to the Science of Reading.

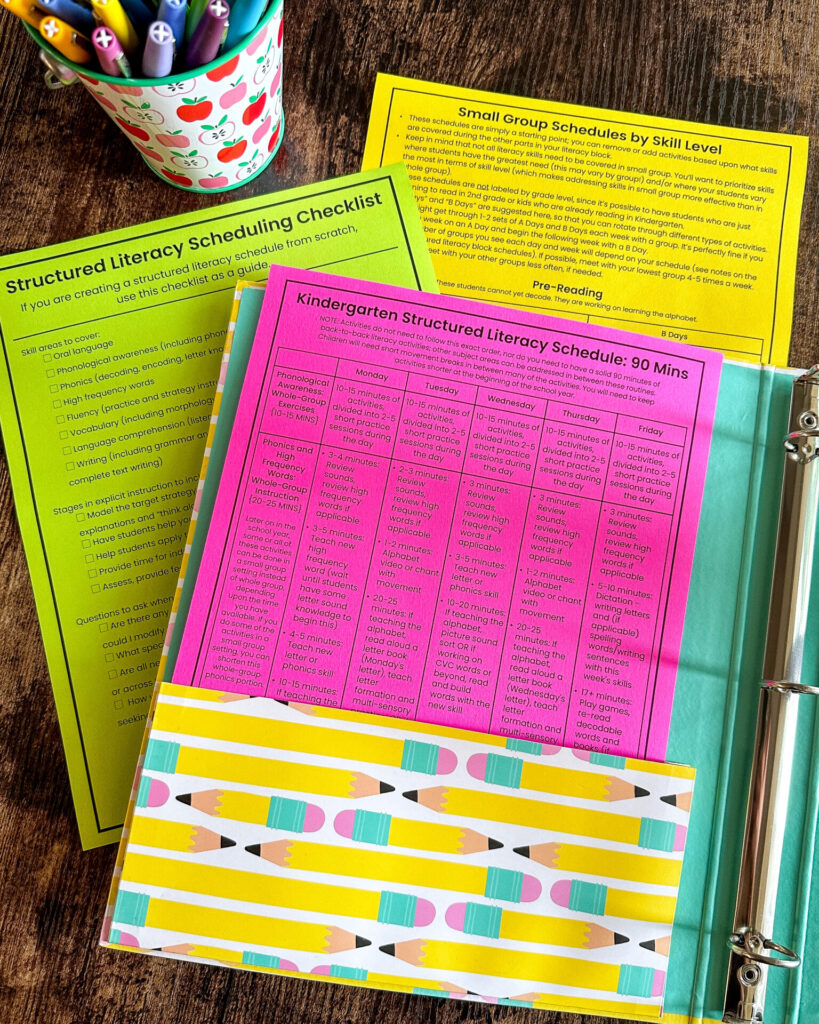

Everything I’m going over in this blog is covered (in more depth!) in a course I offer called “Implementing the Science of Reading in K-2: Blueprint for Your Structured Literacy Block.” By enrolling, you can master the Science of Reading and feel confident you’re giving your students all the skills they need to be successful!

Shift #1: Add in oral language instruction.

Oral language is spoken language, the way we communicate through talking. You are most likely talking to students all day, they are also talking to you, and they talk to one another, too!

Even so, oral language skills still require instruction, especially when we want students to use more advanced vocabulary and academic language.

You can begin by explicitly modeling and teaching conversational skills. These skills include things such as:

- taking turns

- eye contact

- body language

- how to ask questions for clarification

- appropriate voice volume

Oral language isn’t something that should just be taught during your literacy block. This type of instruction should also be added to other subjects like math, science, or art!

For instance, during a math lesson, imagine students are going to work together on solving a word problem. You want to have them turn and talk with a partner. To instruct on appropriate voice volume, say and do something similar to the following:

“When you are talking to a partner, you want to have an appropriate volume. You want to talk loudly enough for your partner to hear you, but not so loud that you’re distracting other students around you. Watch as I model this for you.”

Then, model the appropriate volume you’re looking for with either another adult in the room if available, or ask a student to help you out.

It’s also helpful to show students what not to do. Model what it would sound like to talk too quietly, and explain that this would be hard for the partner to hear. Then model what it would sound like to talk too loudly, and explain that this would be distracting for others around you.

Oral language is just one of the many components I cover in depth in my SoR course.

Shift #2: Intentionally teach vocabulary.

Vocabulary is the knowledge of what words mean and how they are used. Vocabulary is key to a student’s literacy success. When a student is reading a text, their comprehension of that text depends largely on their ability to understand the words in a text! Having a large vocabulary also strengthens a student’s writing and communication skills. And vocabulary knowledge is necessary for students to express their thoughts!

SoR research demonstrates that vocabulary should be explicitly taught. When introducing a new word, do the following:

- Provide a student-friendly definition of the word. You don’t need to have students guess what the word means. Just tell them the definition. (The exception to this would be if you are doing a lesson on context clues where they need to use clues from the text to figure out the meaning of a word!)

- If needed, restate the definition when the word is encountered in a text (i.e. in the middle of a read-aloud).

Research has also shown that a single exposure to a word is not enough. Consider, instead, planning for several days of multiple exposures of the word. This will help reinforce the word and make the meaning “stick.”

Some suggested activities for vocabulary are:

- acting out the meaning of the word

- fill-in-the-blank activities

- matching activities

- games using the new words

- encouraging students to come up with a sentence or question using the new word

Shift #3: Make time for fluency.

Fluency is the ability to read accurately, at an appropriate speed, and with proper expression. Fluency is also essential to comprehension (the whole point of reading!). The more fluent a reader is, the easier it is for them to focus on understanding the text.

Fluency is, primarily, the result of rapid and accurate decoding (which requires phonemic awareness, phonics knowledge, and sight word knowledge). However, there are other elements of fluency, too, like: knowing that you need to pause at commas and periods, reading with expression to match characters’ feelings, reading in smooth phrases, and so on.

Students do learn about fluency by hearing fluent readers read, whether it’s a parent, a teacher, or another kid. But that’s not enough. There needs to be explicit instruction on your end, plus an opportunity for independent practice.

Here’s an example of what a fluency mini-lesson could look like:

- Display a text so that both you and your students can see it.

- State your fluency goal. This should relate back to the definition of fluency – reading accurately, at an appropriate speed, and with proper expression. For instance, the goal could be “Read through the entire sentence smoothly.”

- Model! Show students what a fluent reader looks and sounds like. (“Notice when I read this sentence, I read smoothly all the way to the end of the sentence.”) You can/should also model the incorrect way to do it. (“Listen now as I read incorrectly – all choppy, like a robot would sound.”)

- Provide opportunities for guided practice. Students could read a sentence with you.

- Lastly, provide opportunities for students to practice fluency independently. They could read to a partner or record themselves and then listen to the recording.

For more on fluency, check out the blog “How to Build Fluency With K-2 Students.”

Conclusion

Hopefully these small shifts seem manageable to either add into your schedule or tweak your current routine. If you want to dig in even further on the Science of Reading and make sure that your practices are up to date, click HERE to learn more about my course, “Implementing the Science of Reading in K-2: Blueprint for Your Structured Literacy Block.”

In addition to oral language, vocabulary, and fluency, you’ll also learn about comprehension, phonics, phonological awareness, and writing.

This is an on-demand professional development course for Kindergarten, first grade, and second grade teachers who teach literacy. The course will provide you with an in-depth understanding of the Science of Reading and how to apply that knowledge to create a schedule that supports all of these components we addressed in the blog!

Happy teaching!