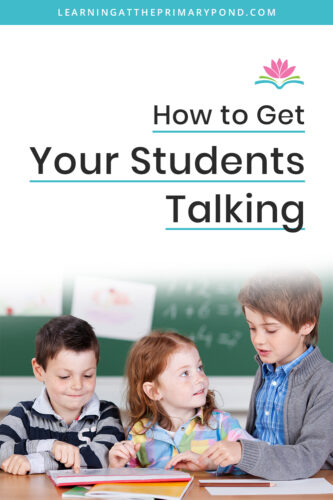

Yes, you read that title correctly! Students innately want to talk, talk, talk. They want to talk to a friend on their soccer team about the tough loss from this past weekend. They want to talk to a classmate to tell them they have the same shoes on. They want to talk to the person (conveniently) across the room to ask what they think is being served for lunch.

So, the big question is – how can you embrace students’ desire to talk? Is there a way to tailor these conversations to be more academic focused?

In this post, I’ll talk about the benefits to student talk (or student discourse as it’s sometimes referred to), how to set it up at the beginning of the year successfully, and activities that lend themselves well to student talk.

Benefits of Student Talk

Let’s take a step back and discuss some of the benefits of student talk:

- increased communication skills

- stronger oral language (which can contribute to reading and writing skills)

- provides students time to process what has been taught

- fosters a sense of classroom community

- helps students make personal connections to instructional material (which helps with retention)

- allows students to learn from one another

- provides opportunities for students to use academic language

As an added bonus, if students are talking, that means less teacher talk! Save your voice and give yourself a much need break once in a while! 🙂

Think for a second about your life as an adult. More than likely, you talk to colleagues or peers throughout the day. Of course, much of this talk may be centered around your lives outside of school – weekend plans, a new book you’ve been reading, a recipe you just tried out – but there are also times where you are probably talking about your actual profession. For example, maybe you and a team teacher are comparing teaching methods of a new math unit or discussing data from a recent student assessment.

Providing students with the opportunity to learn strong communication skills, beginning at a young age, is a gift you’re giving to them!

Setting Up Student Talk

One of the first ways I introduce student discourse is through a “turn and talk.” This is where students have a designated partner to turn toward and talk to, when prompted. During the first couple of weeks in particular, this can also be a community-building exercise. It aids with students getting to know one another – but in an organized way.

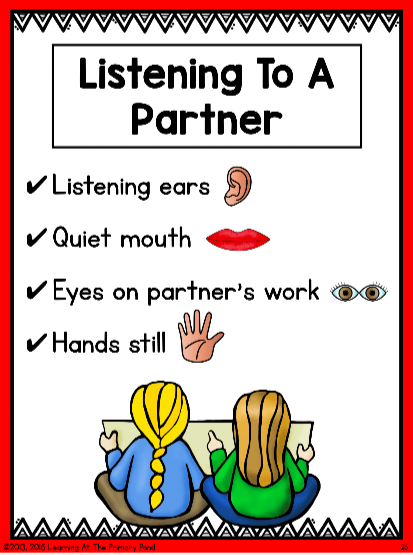

As with any new routine in your classroom, it’s important to begin with modeling. If you have another teacher or support person in the classroom, you can model with them. If not, you can model with another student. Some important things to show include:

- turning your entire body towards the person you’ll be talking to; this allows for appropriate body language throughout the conversation

- giving eye contact to the person you’re talking with; this helps affirm good listening

- deciding who is going to talk first; you can’t have both people just talking at the same time!

- nonverbal cues that can be given while listening; for example, nodding as the other person is talking

One of my favorite things to do is to model how NOT to do student talk with a partner – especially with another teacher friend! Students get a huge kick out of this! We’ll both talk at the same time, turn our bodies away from one another, talk about the most random things… and then of course, I’ll reflect with students about why we shouldn’t do this (and what to do instead)!

After I’ve modeled, students get a chance to practice with a peer. To help facilitate some of the items above, I provide students with a couple of supports. First, I assign them a partner. This helps to eliminate the “I don’t have a partner!” and “I want to be with ______!” or even worse “I don’t want to be with _____!” There are given assignments, and that’s that.

(Sidenote: To learn more about how I choose partners and when I change them, read the blog I wrote entitled Why Is Partner Work Important? How Do You Set It Up Successfully?)

I also usually direct students as to who should go first, i.e. “The person closest to the door is the first speaker.” Again, it helps avoid the argument of both wanting to talk or, on the flip side, having neither student begin and just sit in silence.

Next, I provide students with specifics sentence stems. This helps students get the conversation going and also stay on task. An example of this would be “My favorite character from the story is _____ because _____.”

Eventually, students may learn to just find their own partner, decide independently who goes first, listen to the question from the teacher, and be ready to jump in to the discussion without a given sentence stem. However, getting to that point takes tons of time and practice.

Activities for Student Talk

I’ve already outlined one of my favorite ways to engage in student talk, the “turn and talk.” It’s easy to add this in throughout the day, whether students are on the carpet, at a small group table, or sitting at their desks.

In addition to that, here are some others you could try:

Sharing and Evaluating Writing

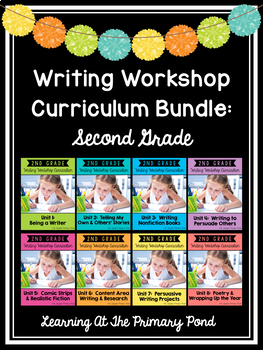

In my Writer’s Workshop units, I first teach students how to share their drawing / writing with one another. Here’s an example of an anchor chart from my Kindergarten resource that outlines this:

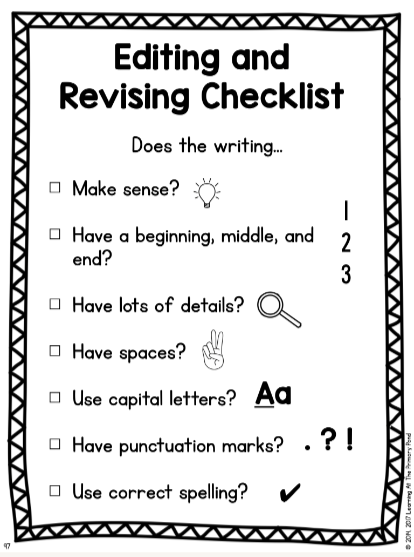

I then take it one step further so that (eventually) students are actually providing feedback to one another. This, of course, helps strengthen their work before a teacher has even laid eyes on it! This is one of the checklists from the Writing Workshop for 1st Grade that students can use with one another:

Using a checklist like the one above allows students to use academic language when providing feedback. So, instead of saying, “That was really good,” they can say things like “Your story had a strong beginning, middle, and end.”

Small Group Discussion

If you’re leading a Guided Reading or small group lesson, there most likely will be some sort of comprehension conversation. It’s easy to fall into the trap of trying to get through a bunch of questions and therefore having the teacher just ask one quick question and have one student answer it. Example, Scenario A:

Teacher: Brynn, who was the main character of the story?

Brynn: Little Mouse.

Teacher: Yep! You’re right, Brynn. Little Mouse is the main character because the story is mostly about him. Okay, Jake – what was the setting of the story?

Jake: A farm.

Teacher: Even though the story mentioned the farm, the city is actually the setting in this story. It’s where most of the story takes place.

If we’re talking analogies, this is more of a tennis drill. The teacher is on one side of the net and the students are in a line on the other side. The teacher “hits the ball”/asks the question, and one student “sends the ball back”/answers the question. That student steps to the end of the line, and the next student has a turn.

So how could you turn this into more of a student discourse? In this next example, the analogy is more like volleyball. The teacher “serves the ball”/asks the question, but then all students are on the other side of the net, “passing to one another”/engaging in student talk. Check out this example in Scenario B:

Teacher: Who was the main character in the story?

Brynn: I think the main character of the story was Little Mouse.

Jake: I agree with Brynn because most of the story was about Little Mouse.

Naomi: I also agree with Brynn and Jake that Little Mouse was the main character. The story also talked about Mr. Rooster but not as much as Little Mouse was talked about.

Teacher: What was the setting of the story?

Lennon: I think the setting of the story was the farm.

Jake: I respectfully disagree with Lennon. The story started on the farm but then Little Mouse went to the city right away. Most of the story was about Little Mouse traveling around the city.

Brynn: I also think the setting was in the city because this is where Little Mouse spent most of his time.

Lennon: Yeah, actually now that you say that, some of the story was at the farm but most of the story was in the city. I’m going to change my answer to the city.

Scenario A and Scenario B are quite different, right? In Scenario A, the teacher is the one who is affirming whether answers are correct/incorrect. It also only allows one student to really be engaged at a time. (For instance, when the teacher calls on Brynn, the other students can instantly become disengaged since they know they’re “off the hook” for the time being.)

In Scenario B, however, the students are talking to one another. They are engaged and listening to one another’s responses, pulling evidence from the text to strengthen answers.

With this type of discourse, you’d teach students each response individually (“I agree with…,” “I respectfully disagree with…,” “I’d like to build on _____’s answer”) and provide them time to practice. (It takes a lot of time to get to this point!)

Conclusion

Hopefully this got your wheels turning about how you can promote student talk in your own classroom! With all of this, it is, of course, important to teach students that there is a time and a place for student talk. There are certain times of the day when talk has to be limited, for practical purposes (i.e. you are teaching or students are practicing independently).

If you’re interested in learning more about the Writing Workshop curriculum, which includes tons of opportunities to teach students how to engage in discourse with each other, learn more here!

Happy teaching!