Getting writer’s block is so normal!

But when it happens to our students, it can certainly be frustrating.

We want our kids to make the most of their writing time. We want them to be engaged in active practice, not staring off into space. And we certainly don’t want them interrupting our conferences or small groups every time they need to think of a new topic!

Although getting writer’s block is a very common problem, there absolutely are steps we can take to help our kids. In this post, I’ll share ways to empower students to come up with new topics independently!

Photo Credits: Serhiy Kobyaov, Shutterstock

What Not To Do

Before I dive into ideas about what to do, let’s take a second and explore what not to do. I’ve learned (by trial and error) that these two strategies just don’t help kids learn to think of topics independently.

1. Always giving students a topic or prompt to write about.

Yes, kids will have to answer writing prompts throughout their school careers – and maybe even as adults. But they will also have opportunities to write when they aren’t given much guidance at all.

If we get our kids “hooked” on always having a prompt or topic to write about, many of them will come to believe that they can’t come up with topics independently. And this is definitely not something that we want!

I always begin the school year by having kids write about self-selected topics. I want to foster that independence from the start, even if it’s a bit challenging for them at first.

Later on, once the kids have become a bit more comfortable with choosing their own topics, I begin introducing prompts. But throughout the rest of the year, kids still choose their own writing topics more often than not. (Curious about how I do this? Read more about how I incorporate choice into my writing workshop in this post.)

2. Using very specific prompts/questions to guide a student into a topic.

When a student is sitting there and not writing, it’s very tempting to start asking, “What did you do this weekend? You went to the state fair, didn’t you? Could you write about that? And how you saw the ponies?”

This specific line of questioning might fix the problem. But it’s only a temporary fix. After the child finishes writing about seeing the ponies at the fair, she’s likely going to get stuck again.

I am definitely guilty of falling back on this type of questioning. Especially if I REALLY need to start a writing conference or small group, and I just want to help a student get started quickly.

But it’s so much more powerful when I prompt for strategies rather than ask a series of questions. I’ll expand on each of these later on in this post, but here are some things I can say instead of asking specific prompts or questions:

- Is there a chart/poster in the room that can help you?

- Where can you look if you aren’t sure what to write about?

- Are there any books that might give you an idea?

- What have you done before when you got stuck?

- What have your tablemates done when they got stuck?

I do want to note that students with special needs sometimes have an extra-hard time coming up with topics independently. If I have a student who really and truly struggles (even after I’ve implemented all the strategies below), I will provide “guided choice.”

When I provide guided choice, I choose 2 or 3 topics that I think may interest the student. I may also show the child an interesting photo (related to the genre) and let her look at it to see if it sparks any ideas.

Fostering Independence

Okay, so now let’s talk about what we should do to help students become more independent and self-directed when writer’s block hits!

A good first step is to use those verbal prompts I listed in the previous section (“Is there a chart/poster in the room that can help you?” etc.).

Also, to prevent kids from getting “stuck” and becoming unproductive in the first place, teach a few different minilessons that specifically focus on this problem. Most kids won’t magically become self-directed, so we have to model and teach strategies that they can use to solve this problem on their own.

The following three sections (Anchor Charts, Beginning of Unit Brainstorming Sheets, and Mentor Texts) cover strategies that you might share with students during those minilessons.

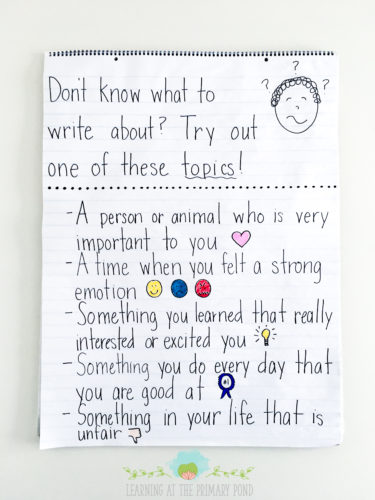

Anchor Charts

Relatively early on in the year, we make an anchor chart with strategies for tackling writer’s block.

The chart can be general, listing things like:

- Read some mentor texts for ideas

- Look at your brainstorming sheet

- Ask your table partners what they are writing about

The chart can also be more specific, like this:

Regardless of how you and your kids make the chart, you’ll want it to become a “living” part of the classroom. When you model writing, show the kids how you refer to the chart. And continue to do so throughout the whole year, not just at the beginning. Add onto the chart periodically, too. Otherwise, it can just become another thing on the wall that the kids ignore!

Beginning of Unit Brainstorm Sheets

In many of my writing units, I have students come up with multiple ideas at the beginning of a unit. We explore the genre a bit first, and then kids spend time coming up with possible topics.

Occasionally we make a class chart of ideas. But more often, I have the kids create their own personal lists. They keep these in their writing folders, and they can refer back to them throughout the unit whenever they finish a piece.

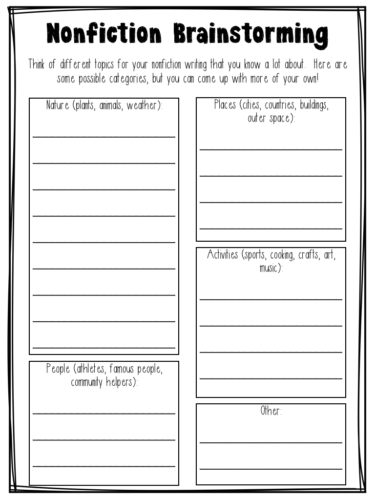

Here’s an example from my second grade nonfiction unit – kids come up with different topics in the subcategories of nature (plants, animals, weather), people (athletes, famous people, community helpers), places (cities, countries, buildings, outer space), activities (sports, cooking, crafts, art, music), and “other.”

It’s also helpful if you print the brainstorming sheet out on cardstock or colored paper so it doesn’t get “lost” in the kids’ writing folders. 🙂

Mentor Texts

Published books can serve as a great resource for kids who have writer’s block! If you keep a basket of mentor texts within the genre that students are working on, the kids can independently decide to look through the basket when they can’t think of a topic.

I make sure I do a lot of modeling of this before I “let them loose” with the mentor texts, however. I don’t want kids to think that they should either a) copy the books verbatim (yep, that’s happened in my classroom before!) or b) choose the exact same topic as one of the books.

Instead, I think aloud as I use a mentor text to get an idea for an original piece of writing. Here are some examples of what this might sound like:

- “Let me look through this book about dolphins for some ideas. OH! This picture on the predators page shows a shark. I can write a book about a shark!”

- “This story is an example of a personal narrative. I’m going to skim it quickly and see if it reminds me of anything that happened in my own life. Hmmm…oh, I see the little girl getting an ice cream cone on this page. That reminds me of the time when I got a huge ice cream cone – and then it fell right onto the sidewalk! I was so disappointed. I’m going to start a new story and write about that.”

Conclusions

All of the strategies in this post have helped my students in the past. Additionally, one of the most powerful things we can do is to show empathy for our students when they experience writer’s block.

Even if you’re not a novelist, you’ve probably experienced writer’s block in your lifetime. Maybe you had to write a difficult email to a parent and just weren’t sure how to begin. We’ve all been there! When I “normalize” writer’s block for my students and then suggest strategies to help, they’re a little more willing to try out a new topic.

Looking for writing units to help you foster this kind of independence in your students? Check out my K, 1st grade, or 2nd grade writing bundles below. Happy teaching!

Resources:

Mermelstein, L. (2013). Self-Directed Writers. Portsmoouth, NH: Heinemann.