Growing up, I was not exceptionally strong at comprehending what I read. Could I decode? Yes. Could I retell enough to make a teacher think I understood a text? Yes. But was I a strategic comprehender? Definitely not!

The main reason for my comprehension weakness, in my opinion, is simply that I was never explicitly taught any comprehension strategies. I remember class discussions about the content of different texts. But I never, at any point, recall learning how to make inferences, consciously ask questions while reading, or determine the importance of information.

As a result of all this, I struggled with certain academic tasks. I often had to read an entire novel a couple of times, because I was not actively making sense of the ideas during my first read. I was also a terrible note-taker. Because I had not learned how to figure out what information was most important, I wrote EVERYTHING down! (And I mean everything – I filled up notebook after notebook!)

The funny part is that I was never considered a struggling reader – I was actually a “straight-A” student. I was fortunate enough to have supportive parents, a decent memory, and coping strategies.

Still, not being taught comprehension strategies affected me negatively – so I can only imagine the impact this would have on a child who does not have the same advantages that I did.

Not learning active comprehension strategies could be completely devastating for a child who struggles with decoding, is impacted by poverty, has a language disorder, or who has a hard time with reading for some other reason. Those students absolutely must have a toolkit of active comprehension strategies that they can apply to get the most out of the texts that they read.

But beyond struggling readers, all kids benefit from learning comprehension strategies. Our students are growing up surrounded by technology, and they are being constantly bombarded by images and text. They need to learn to make sense of it all in order to lead productive, healthy lives.

I know that the Common Core State Standards do not explicitly mention comprehension strategies – but I do not believe that this means we should not teach them! And here’s a quote from Harvey and Goudvis’ Strategies That Work (2007) that highlights the importance of strategy use for comprehension:

“Pearson, Dole, Duffy, and Roehler (1992) summarized the strategies that active, thoughtful readers use when constructing meaning from text. They found that proficient readers:

- Search for connections between what they know and the new information they encounter in the text they read

- Ask questions of themselves, the authors they encounter, and the texts they read

- Draw inferences during and after reading

- Distinguish important from less important ideas in text

- Are adept at synthesizing information within and across texts and reading experiences

- Monitor the adequacy of their understanding and repair faulty comprehension

Pressley (1976) and Keene and Zimmerman (1997) added sensory imaging to this list of comprehension strategies.”

I believe that it’s our responsibility to empower children to become “active, thoughtful readers” by teaching them these strategies. And I don’t think we should wait until they can decode fluently in order to teach these skills! We can lay the foundation in Kindergarten and first grade by modeling and guiding them in using these strategies with the texts we read aloud (and the texts they read independently, as much as possible).

Of course, teaching a 5 year old to infer and synthesize is no small task. For ideas about how to teach each of these strategies in a “primary-friendly” way, keep reading!

Making Connections

When we’re talking about making connections, I don’t mean comments like, “The character’s sweater is red, and MY shirt is red, too!” 😉

But of course, you are naturally going to get those types of connections from 5, 6, and 7 year olds. When I teach my kiddos how to make connections, I allow those comments for a day or two. But then I really begin to challenge them to ask themselves, “So what?” I require that when they make a connection to a text, they must also explain how the connection helped them better understand the text.

I begin by teaching students what schema is, so that they can make text-to-self connections and use background knowledge. We start with fiction, and I read them Julius, The Baby of the World, by Kevin Henkes. (This is a great book because most students can relate to feeling jealous at some point in their lives.) We talk about how our own experiences and emotions inform our understanding of characters’ emotions – we can understand why a character feels jealous because we, too, have felt jealous before. Then, I teach students how our schema can help us understand characters’ actions (our own experiences can help us figure out why a character acted a certain way).

When we move on to nonfiction, we practice considering our background knowledge before (and during) our reading of a text. I always make sure to teach students to revise their background knowledge, since not all prior knowledge is accurate. I love using the RAN strategy instead of a K-W-L, because it has a category for “We Don’t Think This Anymore.”

For detailed lesson plans on how I teach K-1 students to make connections, check out my schema unit and my text-to-text connections unit.

Asking Questions

Asking questions can be tricky to teach, so I start working on this skill on the second day of Kindergarten. Yes, I’m serious! I use a Student of the Day routine and model asking the “Student of the Day” questions about his or her favorite food, toys, games, TV shows, etc. After a couple of days, the kids are ready to ask their own questions, and they are excited to do so!

When I ask students to apply this skill to an academic context, I teach them the concept of “thick” and “thin” questions. Thin questions can be answered easily, with a briefer response. Thicker questions, on the other hand, may require us to look multiple places in a text, and there may not be one right answer. For lessons on how to teach questioning, click here.

Inferring

Inferring sounds like it would be difficult to teach little ones, but in reality, kids make inferences all the time. For example, if you show your students a photo of a child who has a thermometer in her mouth and looks sad, the vast majority of your students will immediately understand that the child is sick.

I like to teach inferring using photos, and then move on to texts. I also think it’s important to teach students how to infer for a specific reason, rather than to infer “in general.” For example, we can teach students to “infer how a character is feeling by paying attention to what they do and say.” For ideas on teaching inferring and a detective activity, click here.

Determining Importance

This, I think, is a difficult skill to teach little ones! I try to give students practice with this on a consistent basis throughout the year (and across subject areas), by asking questions like:

- If you could tell a friend only two facts about this topic, what would you share with them?

- What was the most important thing you learned today?

- What was the most important step in the science experiment we did? Why?

- What was the most important thing you did over winter break? Why?

Synthesizing

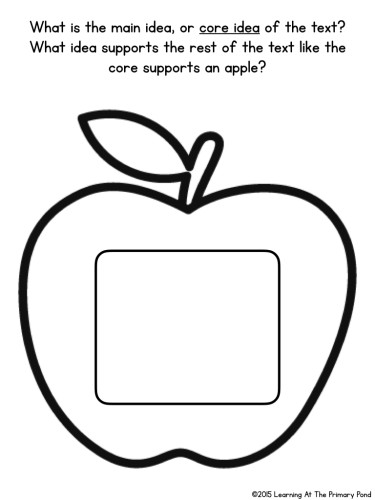

Synthesizing within a text helps readers come up with the main idea. I do tons of modeling when teaching main idea, and I also use this graphic organizer:

Apologies for the poor quality – it’s an old photo! But what I like about this organizer is that it gets the idea across that there are lots of events (or facts) in a text, and we can use those ideas to come up with one main, core idea (like the core inside an apple supports the rest of the apple).

If you like the apple core analogy, click on the image below to download this graphic organizer for free:

Monitoring

When I teach students to monitor their comprehension, I integrate it with the skill of asking questions. I want my little readers to be consistently asking themselves, “Do I understand what is happening so far?” and using strategies when the answer is “no.”

During whole group readalouds, we can support students’ self-monitoring by planning for frequent turn and talks. Saying something like, “When readers go through a text, they pause every so often and ask themselves, ‘Can I retell the story/information so far?’ Let’s take a minute and see if we can retell the text so far to a partner.”

After the turn and talk, either model a retelling or construct a retelling with students. Then, ask students to evaluate their own retelling (that they did with a partner), on a scale of 1-3 (3 being the best, 2 being okay, and 1 being “needs work”). You might have students always giving themselves 3’s at first, but like many skills, this takes time and is developmental.

Visualizing

Visualizing is especially FUN to teach little ones! Read students a poem or part of a story without showing them any pictures. Have them sketch, on a sticky note or sheet of paper, what they are imagining. Eventually, teach students to add to their drawings or even create a set of 3 to depict the beginning, middle, and end of a story. For complete lessons on teaching students to create mental images, click here.

Conclusions

This post has really just scratched the surface of teaching comprehension strategies, but I hope you got a couple of new ideas to try out with your little ones!

With these comprehension strategies (as with anything), I focus on moderation. I want my students to learn to actively use these strategies, but I don’t require them to memorize the names of the strategies. We also spend plenty of time talking about the actual content of text.

The lessons I mentioned in this post can be found in my Reading Comprehension Strategies Curriculum for K-1. This is a series of 9 units that can be purchased individually or as a discounted bundle. Each unit is based around a foundational comprehension strategy, and the units address the fiction and nonfiction Common Core Standards. To read more about the lessons, click on the image below:

I’m thankful that becoming a classroom teacher and (and then a reading specialist) has made me a more intentional (and better) adult reader. I hope that by teaching our students to use comprehension strategies at a young age, we can help them avoid the problems that arise from not having the tools they need to navigate complex texts.

Harvey, S. & Goudvis, A. (2007). Strategies that work: Teaching comprehension for understanding and engagement (2nd edn). Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

THIS IS SUCH A GOOD BOOK! HAVE IT! 🙂 Used it in college!