Dyslexia is the most common learning disability. It is the #1 reason why students have trouble learning to read. Because of this fact, it’s important that everyone working with students understands what dyslexia is and isn’t.

If you work with kids on a day-to-day basis, you have probably come across students with dyslexia, whether or not you realized it. Or, maybe there are students who you think could have dyslexia but haven’t been diagnosed yet. Whatever the case may be, there are often some misconceptions when it comes to dyslexia.

In this blog post, I’ll explain some of the terminology around dyslexia and how brain activity plays a part in this learning disability. I’ll also help clear up some common misconceptions by naming what dyslexia is (and isn’t!)

If you want to dig even further into dyslexia, that’s covered in a specific module of my Reading Intervention Collaborative, a professional learning environment for K-5 educators.

What’s Happening in the Brain When It Comes to Dyslexia?

To begin, here are two important definitions:

- phonemes = the smallest speech sounds; the building blocks of all words (such as /m/ or /sh)

- learning to read = matching printed letters to phonemes (so when someone sees “cat,” they know the c makes the /k/ sound, a makes the /a/ sound, and t makes the /t/ sound)

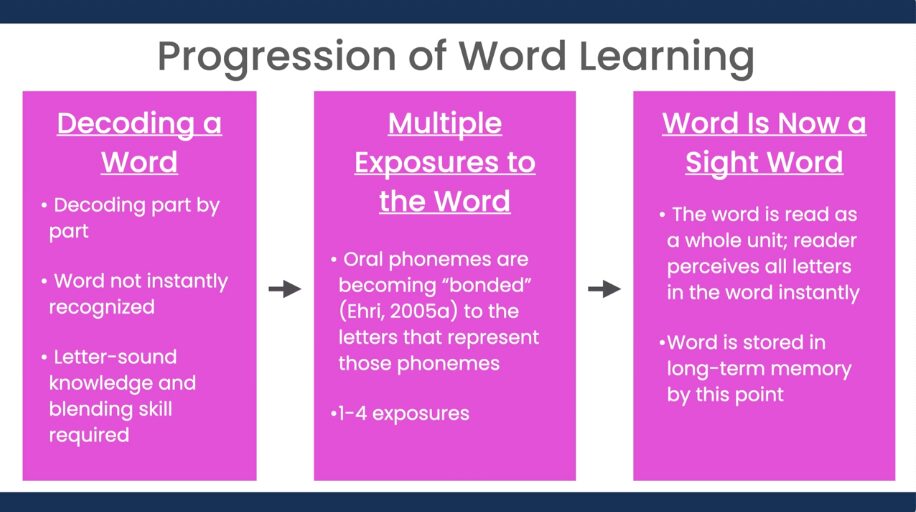

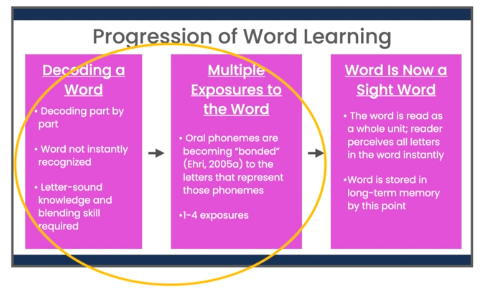

Here’s what the progression of word learning should look like once students have learned phonemes and then are learning to read:

In other words, a non-dyslexic student would use phoneme-grapheme correspondences (letter sound relationships) to decode the word, have 1-4 exposures of correctly reading the word, and then eventually the word will become a sight word for them. This means that they won’t have to sound it out any longer; they will recognize it immediately.

**If you work with students not quite old enough to decode words, I point out in my Reading Intervention Collaborative what some pre-reading signs of dyslexia could look like.

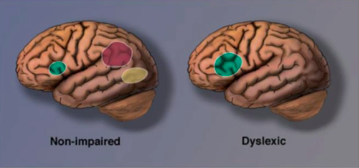

Now let’s talk about what’s going on in the brain of a dyslexic reader. When neuroscientists study the brains of dyslexic and non-dyslexic readers, they notice some consistent differences.

Dyslexic readers have been shown to have:

- Less gray brain matter in the left parietotemporal area, which may contribute to problems with phonological awareness

- A disruption in rear reading systems in the left hemisphere in the brain, which may result in dyslexic readers compensating by using less efficient systems

- Less overall activation of brain areas important for reading

To illustrate these differences in brain function, here’s an image comparing the brain function of a “non-impaired,” or typical reader, with a reader who has dyslexia:

drs-sally-bennett-shaywtiz-on-dyslexia-adaaa/

While most dyslexic readers can learn to decode, many continue doing so manually, rather than reading words automatically.

An analogy for this is the skill of driving:

When you first learn to drive, you’re thinking about every single part of it – switching lanes, turning on blinkers, studying your speed, checking mirrors. It can feel overwhelming and tricky for everyone in the beginning. Eventually, though, a lot of this becomes habitual where you don’t even think about all you’re doing while you drive. It just comes naturally.

The same is true for reading. When you first learn to read, you think about every single letter and sound. You may need tons of guidance and support. It feels like a lot and requires so much focus! Eventually, reading becomes natural and you don’t really even think about it while doing it.

With a dyslexic reader, they can get stuck in that initial “learning to read” phase for longer. Even after lots of practice, some dyslexic readers still struggle with fluency. In some ways, they get stuck in the first two stages of “Decoding a Word” and “Multiple Exposures to the Word:”

This is one reason why you may notice them sounding out the same word over and over again. Dyslexic readers may only connect a few letters in a word to their sounds, so the word isn’t sticking in long-term memory.

What Is Dyslexia and What Is It Not?

Dyslexia IS a specific learning disability. (And likely the most common learning disability.)

Dyslexia IS NOT a visual problem that involves reading letters or words backwards. This is a myth. Letter reversals are normal and typical in many children, up until about age 7/8. Students with dyslexia often reverse letters/numbers, but that’s not because of their dyslexia. If letter reversals persist longer, however, this can be a potential red flag.

Dyslexia IS a result of problems with phonological processing. As I outlined above, dyslexic brains are wired a little differently. Many dyslexic people are believed to have a phonological “deficit” or difference.

Dyslexia IS NOT the result of poor teaching. Again, dyslexia is related to the wiring of the brain, not because a student didn’t receive enough high-quality instruction.

Dyslexia IS a language-based disorder and can impact speaking, reading, spelling, and writing.

Dyslexia IS NOT related to intelligence. People with dyslexia can, of course, still be highly creative and intelligent. Unless something else is getting in the way, they can discuss and comprehend texts being read aloud to them – even texts that are much more difficult than what they can decode.

Dyslexia IS something that lasts throughout a person’s life. It cannot be outgrown. Dyslexia, however, can be treated and there are definitely ways to help dyslexic readers. In Reading Intervention Collaborative, I explain in detail various supports that can be given to dyslexic readers to help them be successful.

Dyslexia IS NOT limited to students who score far below average on reading tests. Certain dyslexic students “work around” their struggles and find other ways to be successful in reading.

Dyslexia IS treatable. Effective, evidence-based structured literacy instruction and intervention is crucial for improving outcomes for dyslexic students. The earlier dyslexia is identified, the better, so that a child can receive the support they need.

Conclusion

Thank you so much for taking the time to read this blog post! All educators need to know the signs of dyslexia and the importance of early intervention so that students can receive the intervention they need, so feel free to share this article with colleagues!

And if you’d like a dyslexia fact sheet to download and keep, you can grab one for FREE at this link!

One last important thing to know: there are varying degrees of dyslexia. Some children have a slight difficulty learning letters/sounds, and it’s somewhat difficult for them to decode words. But then there may be other students who really struggle with reading basic words. They have a hard time with everything related to literacy, and it significantly impedes their academic progress. Then, of course, there are students in the middle of that spectrum.

Another thing I want to mention is that there are multiple reasons why a student could be struggling with reading, not just dyslexia. To read more about these other reasons, check out my blog post on the “Find the Why” method, designed to assist struggling readers.

Learn more about dyslexia and how to help all struggling readers in the Reading Intervention Collaborative. As a member, you’ll have access to all of this information, a network of coaches, and a community of other educators who are in the same boat as you!

Happy teaching!